황중통리(黃中通理)

학고재 전시 기획실

「군자는 황색으로 안을 채우고 이치에 통달(黃中通理)하여 바른 자리의 중심에 선다.

아름다움을 내면에 길러서 온몸에 펼치고 사업에 뻗어나가게 한다.

미(美)의 극치라 하겠다!」

주역 곤괘에 나오는 말이다. 학고재 ‘춘추’ 4번째 주제를 황중통리로 잡았다. 곤괘는 땅을 상징하는 괘다. 사람에 있어서는 여성을 상징하고 어머니를 상징한다. 땅은 끝 모를 두터움으로 산천초목을 싣고 살린다. 어머니는 가 없는 사랑으로 자식을 낳고 기른다. 주역은 그것을 충만한 황색이라 했다.

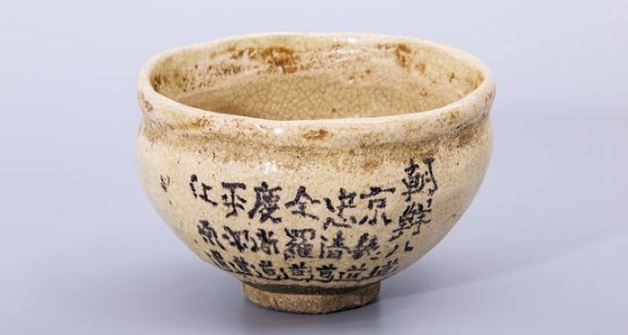

황색은 땅의 정색이다. 학고재는 조선 전기 16세기에 만들어진 우리의 정호다완(井戶茶碗)이 한없이 깊고 끝없이 두터운 대지의 색을 머금고 있다고 생각했다. 자신은 뒤로한 채 오직 자식만을 위하는 어머니의 덕이 그 안에 담겨있다고 생각했다. 우리는 그동안 그 가치를 제대로 살피지 못했다. 참으로 아쉽다. 소홀히 취급한 탓일까. 이때 만들어진 정호다완은 지금까지 남아있는 것이 많지 않다. 그마저 모두 일본인 손에 있다. 국내엔 전무하다. 제작된 도요지와 확실한 용도도 아직 합의된 정설이 없다. 연구하고 자리매김해야 할 일이 남아있다. 이번 전시에 전성기의 정호다완은 출품하지 못했다. 대여해올 방법이 없었다. 다만, 그와 연관성이 있는 작품 3점을 출품하는 것으로 위로를 삼을 뿐이다.

전통의 가치는 그것이 창조의 뿌리가 된다는 데에 있다. 도예가 김종훈 선생은 이 시대 어둠으로 남아있는 도예계의 한구석에 등불을 밝힌 분이다. 도예 작업에 발 들인 날부터 지난 20여 년 동안 정호다완을 연구하고 제작해왔다. 일본을 이웃처럼 드나들며 중요한 정호다완을 모두 실사했다. 그와 관련된 전시는 언제 어느 곳이든 놓치지 않고 찾아가서 실견했다. 정호다완이라는 꽃봉오리 속에 숨겨진 꿀물을 저작(咀嚼)하기 위한 과정이었다. 이 여정을 거듭하여 내면에 쌓은 자양을 이번 전시에 70여 점의 정화로 토해냈다. 보는 이들은 이 작품에서 축적된 세월의 흔적과 갈고닦은 생각의 깊이를 확인하게 되리라 믿는다. 황중통리의 뜻을 도예로 해석해 냈다고 하겠다.

대지의 정색이 황색이라면 조선 시대를 품은 색은 백색일 것이다. 18세기 백자 항아리는 조선의 심성을 대변하는 백색 도자기다. 이번 전시에 18세기의 듬직한 맏며느리 닮은 달항아리 1점과 김종훈 선생의 겨울날 시골마을 뒷동산에 소복이 쌓인 흰 눈 같은 백자 항아리 6점을 함께 펼쳤다. 전통의 우물에서 길어 올린 기름으로 현대를 이끌어 갈 등불을 켜고자 한 것이다.

우리의 황색 다완과 백색 항아리는 서릿발처럼 차갑거나 송곳처럼 뾰족한 색이 아니다. 겨울날

우리네 황톳빛 들녘 위에 느릿느릿 내려 쌓이는 함박눈처럼 따스한 색이다. 오늘을 품어주고 내일을 열어갈

복된 색이다.