공회전: 맴도는 도상들

박미란 | 학고재 큐레이터

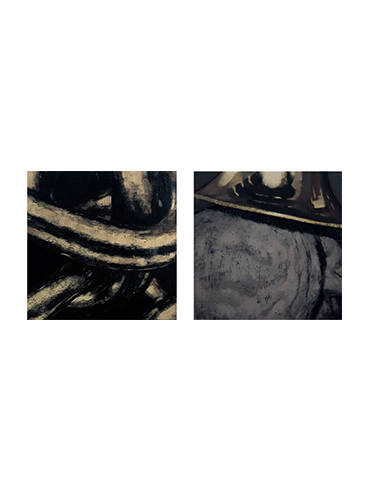

스산한 풍경이 펼쳐진다. 공간이 인물을 잠식한다. 인체의 형상은 사물과 뒤엉키거나 배경 속에 흩어진다. 낮은 채도로 조밀하게 묘사한 화면 위, 상징적 도상이 지속적으로 등장한다. 현실의 풍경을 분해한 조각이다. 이동혁은 장면을 재구성하며 사유를 정제해 나간다. 관념이 형상화한다. 작업을 관통하는 주제는 믿음에 대한 의구심이다. 종교적 맹신, 집단의 관습에 관한 이야기다. 새로운 관점을 얻으려면 아는 것을 불신해야 한다. 시야 너머 진실을 찾아내기 위함이다.

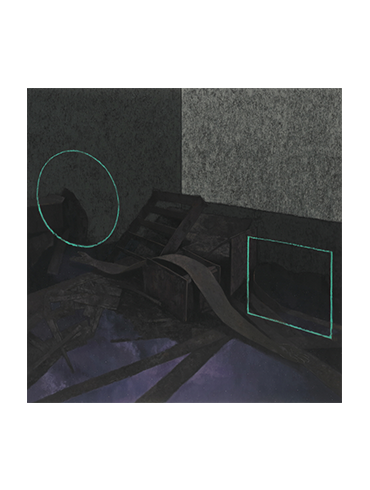

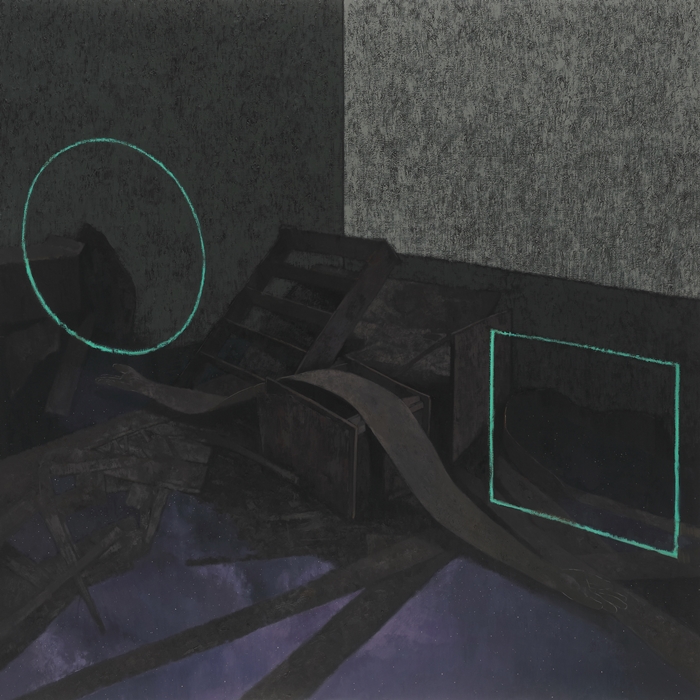

지난 초여름 방문한 낯선 폐 교회의 풍경을 회화로 담았다. 내려앉은 천장의 잔해가 무겁다. <하늘에서도 1>(2020)의 화면 중앙에 놓인 목재가 구부러진 팔의 형상을 띤다. 양손에

저울질 하듯 띄운 원과 사각형은 각각 이상과 현실을 뜻하는 기호다. 땅이 있어야 할 자리에 찬란한 별이

빛난다. 현실의 몸으로 디딜 수 없는 기반 위에서 많은 이가 이상을 꿈꿨을 테다.

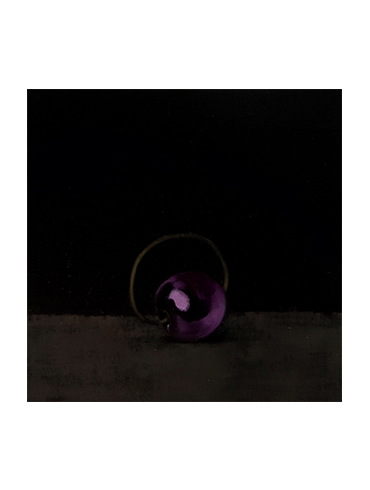

이동혁의 도상들은 서술적이다. 내포한 의미를 가리키는 저마다의 표지다. 일상에서 통용되는 기호는 아니다. 기독교 문화에서 사용하는 상징이 많다. 모태 신앙으로 태어나 종교인으로 자란 작가에게는 익숙한 요소다. 그러나 관객을 위한 충분한 단서를 제공하지는 않는다. 특정 문화에서 끌어온 도상들은 해당 집단의 관습을 투영한다. 주어진 맥락 내에서만 기능하며, 바깥으로 떨어져 나오면 의미가 흐려진다. 올바른 독해의 방향이 주어지지 않으면 관점에 따라 달리 읽힌다. 모호한 기호가 된다.

도상들이 유령처럼 화면 위를 맴돈다. 설명을 최소화한 상징들은 마치 해답 없는 수수께끼 같다. 허무와

당혹의 감정 가운데 비로소 작가가 드러내려는 핵심이 보인다. 옳은 것이라 믿어온 원칙의 실효성에 관한

질문이다. 나아가, 맹목적인 믿음의 당위성에 대한 물음이다. 이동혁의 화면은 바른 해석을 강요하지 않는다. 불분명한 설명으로

답을 유예한 채, 회화의 물성에 집중하고 장면 자체의 감각을 전달한다.

교훈을 주입하는 대신 능동적 판단을 고무하는 태도다. 정보를 적시하지 않는 풍경은 역설적으로

더욱 풍부한 해석의 가능성을 연다. 관습의 울타리에서 한 걸음 물러서면 완전히 다른 시각을 획득할 수

있다.

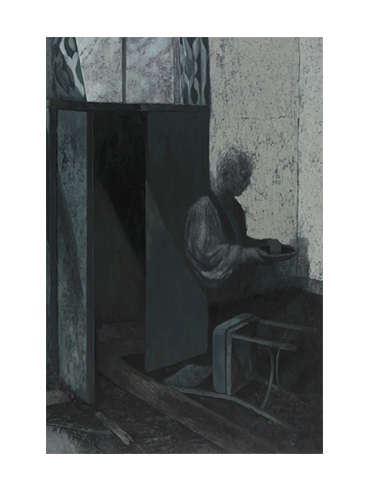

부서진 교회의 풍경을 마주한 작가는 공포와 함께 안도감을 느꼈다. 품을 이가 없는 신당은 무너지게 마련이다. 사람을 위한 장소이기

때문이다. 이동혁이 재현하는 대상은 신이 아닌 신자며, 현실의

공간과 사물이다. 절대자가 부재하고, 선악의 기준이 복잡한

세계다. 모두가 완벽한 원을 이루지 않아도 괜찮은 곳이다. 관념의

도상은 여전히 현실의 풍경 위를 맴돈다. 다만, 수용과 해석의

범주가 열려 있다. 서늘한 풍경이 속삭인다. 신뢰에는 맹목성이

없어야 한다. 변화는 늘 의문에서 시작되는 법이다.